The answer lies in a spring festival of Japan which is not cherry blossom viewing

The mention of spring in Japan instantly brings to mind the pink blush of Sakura, of the merriment of ohanami picnics under the beautiful canopy of cherry blossom. Come spring and the market is flooded with cherry-blossom themed products, from Starbucks’ Sakuraful Frappucino to Asahi’s cherry blossom beer, from Calbee’s sakura potato chips to sakura udon. (And, yes, of course, there are plenty of sakura variants of Kit Kat!).

While the accuracy of sakura being the very embodiment of spring season in Japan is undeniable as is the immense importance and popularity of ohanami, there is a lot more to the Japanese spring than cherry blossom.

So, lend me your ears eyes and let me tell you about the popular festival which marks the beginning of spring in Japan – Setsubun no Hi.

Also known as the Bean-Throwing Festival, Setsubun no Hi is held on the last day of winter, which usually falls on February 2, 3 or 4. Literally meaning “seasonal division”, Setsubun was traditionally held each time the season changed, which in Japan is four times a year. Over time, though, only the setsubun before the start of spring came to be widely celebrated, as it closely follows the New Year (based on the Chinese lunar calendar).

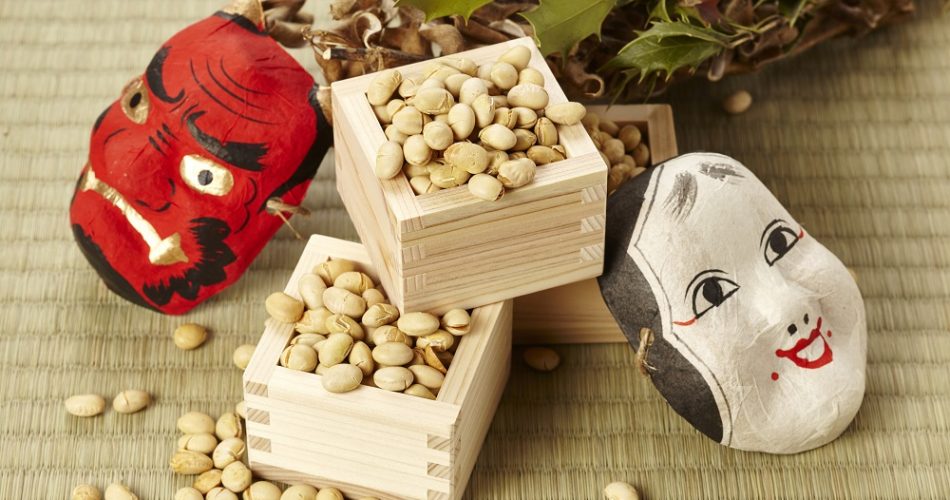

Visit any temple and you’ll see people throwing roasted soybean at an imaginary demon or a person wearing a demon mask while yelling “oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi!”. Sounds interesting and fun, eh? But why do people dress up as demons and throw beans on a day which marks a change in seasons? Let’s find out.

Unmasking the Oni

In China and Japan, it is believed that misfortunes are caused by demons, or “oni”, who appear at the crossroads between seasons. Indeed, with the change in season, people often tend to be more vulnerable to catching diseases and hence, the rituals of this festival are meant to dispel and ward off diseases and other forms of ill-luck.

The practice of purging one’s house of oni is, in fact, adopted from a similar New Year’s Eve ritual in China. Traditionally, the toshiotoko (年男; the male who was born in the corresponding animal year on the Chinese zodiac) or the male head of the household dons the oni mask to symbolise the demon. The rest of the family gathers at the front door to throw roasted soybeans at the “oni” while yelling “oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi!” (鬼は外、 福は内!) which means ‘demon out, fortune in’. This ceremony is recreated in temples throughout Japan and sometimes in schools as well, where the principal or the teachers may dress up as oni.

Soybeans – Lady Luck’s favourite snack

It is clear why Setsubun is also called the Bean-Throwing Festival. But why, out of everything possible, do soybeans have the power to drive away demons?

To answer this, we need to look at Chinese numerology, where a lot of concepts come in fives to correspond to the five elements – one of which is of the “5 most important cereals”. Among those, soybeans (大豆 daizu, literally ‘the big bean’), were considered particularly potent as they were believed to contain the spirits of all the cereals combined, and henceforth, make for effective weapons against oni. Thus, sprouted the ritual of mamemaki, which is the Japanese term for throwing soybeans at demons.

Interestingly, in a clever wordplay by the Japanese, mame (豆), which is bean, is a homophone for mame (魔滅), which means “destroying evil”. (Next time, drink your soymilk with pride!)

The (not-so-humble?) soybeans serve another purpose as fukumame (meaning good fortune beans). After the mamemaki is over, it is customary to count and eat the number of soybeans equal to your age plus one to attract good luck and health for the coming year.

Stores all over start selling roasted soybeans prepared in packages (sometimes with a complementary oni mask!) in the days counting up to the festival. It’s never a bad idea to get a couple of packets for yourself! (they make for pretty decent snacks as well, trust me 😉)

The good-luck sushi

Another Setsubun activity which involves eating (yay!) is the consumption of ehou-maki (恵方巻き), which is a giant sushi roll. Rolled in the nori seaweed are the 7 ingredients of this special sushi – Japanese omelette, shiitake mushrooms, carrots, squash, cucumber, tofu and eel – which represent the seven gods of fortune. This tradition which emerged in the Kansai region and later spread to the rest of the country, involves eating a whole ehou-maki facing the lucky direction (which varies every year) in complete silence and in one go. Cutting the roll is forbidden as it would mean cutting down the fortune. So much for luck!

A lot of temples and shrines host the celebrations with all the rituals and traditions, especially the bigger ones like the Heian Shrine in Kyoto or the Sensō-ji Temple in Asakusa, Tokyo. Apart from the elaborate festivities, celebrities are often invited to take part in the rituals. It’s a great idea to head over to one of these and enjoy Setsubun no Hi in the truest sense, or if you’re like me and want to beat the crowd, you can also head over to smaller shrines and temples. Every district has its website which gives details on various local festivals (usually, you would need to translate but it’s worth a try.)

Comments